Sunday, November 1, 2009

What you don't know about your camera can hurt you.

As much as I would love to summarize the entire History of Photography course I took in college in one blog, I want to talk mainly about why knowing a thing or two about optics can change the way you photograph.

Since the advent of the view screen, many point and shoot cameras (thanks to the habits of their consumers) have dropped the viewfinder all together. Even the Nikon D-300 I shoot with has the option of using Live View and skipping the viewfinder all together. This is just one example of how photography continues to adapt to the needs of the user. The SLR (single lens reflex) came from a similar revision that allowed the photographer to see exactly (or at least a more accurate view) of what would be captured on the film plain. Today film has given way to digital sensors and a whole host of people owning digital SLR's. Sadly though, many have fallen prey to the fallacy that by owning a camera with more megapixels, you will instantly take better photos.

As with all technology, operator error is the main reason for poor results. So for all of you that have said to me "I really like photography, I wish I knew more about it." Here you go. Free, uncensored advice from a pro on how to subtly improve the images you create. So let's start right now with something simple.

Depth of Field

Since Wikipedia already exists, you'll need to use the link above for a scientific perspective and exact definition of Depth of Field (DOF). Let's talk about the application of this technique. (And some other more advanced stuff just for fun).

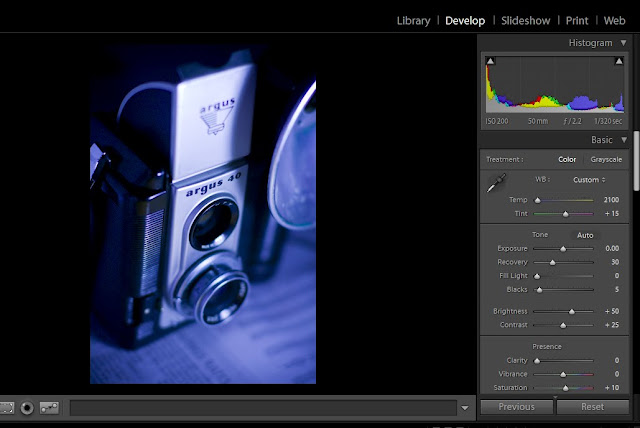

The image you see here is of an twin lens Argus 40. Use the link to learn more about the camera, it's history and see images of a mint condition one (mine is beat up somethin' terrible) and images made by this great little camera. I thought this would be appropriate subject matter since it's one of the precursors to the SLR. The image was shot "wide open." The exposure is 1/320s @ f2.2 . The lens is a 50mm (Standard) which can actually go as wide as F1.4 but I wanted to make sure I got the entire brand name in focus. My light source was a compact florescent bulb about 5 inches to the right of the subject and a folded piece of white paper for a fill card on the left. The newspaper is shown below the Argus 40; it just felt right to show two antiquated but completely functioning objects together.

Can you see the isolation that shallow DOF brings? Nothing is in sharp focus outside the words Argus 40, and even there sharpness begins to fall off at the 40 ever so slightly. The newspaper is illegible (which wouldn't be the case if I was shooting at an equivalent exposure like 1/2 sec. @ F 16. At a smaller aperture DOF increases forwards and backwards from the point in which the camera is focused. Depending on your intent, DOF is one of the most important tools in photography. It helps to create a point of interest, is key as a design element, and since it is tied directly to the basic operation of all cameras, crucial for the photographer to know how to use properly. The simple act of knowing what F-stops produce greater and less DOF will revolutionize any beginning photographer. You should be the one deciding your camera's exposure, not the camera. So many of the evolutions in photography (internal metering, auto focus, zoom lenses) are wonderful tools for the skilled user, but they have become handy-caps for the novice. Photography is a science AND art. You cannot do one properly if you neglect the other in this medium.

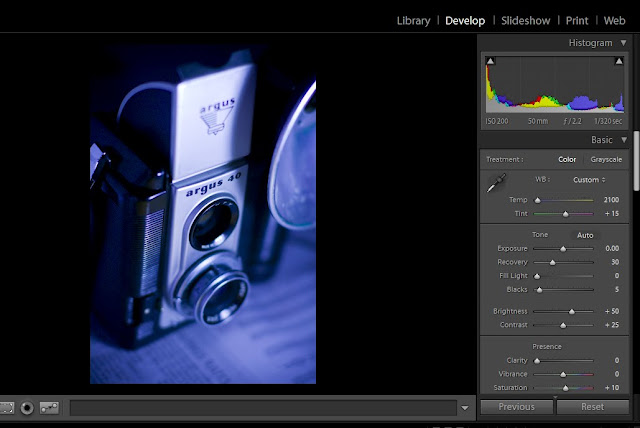

Okay, enough ranting... anyone want to know how to about how to mimic the blue hue in the above image? I use Adobe Lightroom 2.0 to edit my images. As a wedding and portrait photographer I deal in volume and Lightroom has been a saving grace. This year alone I have processed over 64,000 images in record time thanks to this well designed software.

Here is the original image. After importing it into Lightroom I adjusted the settings under the develop tab to these amounts:

Color Temperature: 2100 Kelvin

Tint or Hue: +18 (towards the magenta end of the spectrum)

That's all it takes to fake the look to a tungsten balanced film shot in daylight. You see, the color of light is based on it's Kelvin temperature. Daylight is about 5500K and with the advent of color film came the need for multiple types of film to match the variety of light sources besides the sun. These include your regular 60 watt tungsten indoor lights, your florescent tubes and everything in between. I'm sure it didn't take long after these films hit the shelves that someone shot them outside and found a profound color shift. It's a fun trick and nice throw back to another era of photographic evolution.

If you plan to do the same thing in Adobe Photoshop here's what you need to do:

1. Create a Hue/Saturation layer

2. Use the drop down menu and select Cyanotype (yet another by gone style of yester-year)

3. Increase the saturation to the desired level. I chose 47.

Nostalgia and software aside, photography in all in the application. Tomorrow blog will focus on anther rudimentary element of photography; composition. Until then, please browse the portfolios at Irene Jones Photography Online for examples of how I've used depth of field in my wedding and portrait work.

Since the advent of the view screen, many point and shoot cameras (thanks to the habits of their consumers) have dropped the viewfinder all together. Even the Nikon D-300 I shoot with has the option of using Live View and skipping the viewfinder all together. This is just one example of how photography continues to adapt to the needs of the user. The SLR (single lens reflex) came from a similar revision that allowed the photographer to see exactly (or at least a more accurate view) of what would be captured on the film plain. Today film has given way to digital sensors and a whole host of people owning digital SLR's. Sadly though, many have fallen prey to the fallacy that by owning a camera with more megapixels, you will instantly take better photos.

As with all technology, operator error is the main reason for poor results. So for all of you that have said to me "I really like photography, I wish I knew more about it." Here you go. Free, uncensored advice from a pro on how to subtly improve the images you create. So let's start right now with something simple.

Depth of Field

Since Wikipedia already exists, you'll need to use the link above for a scientific perspective and exact definition of Depth of Field (DOF). Let's talk about the application of this technique. (And some other more advanced stuff just for fun).

The image you see here is of an twin lens Argus 40. Use the link to learn more about the camera, it's history and see images of a mint condition one (mine is beat up somethin' terrible) and images made by this great little camera. I thought this would be appropriate subject matter since it's one of the precursors to the SLR. The image was shot "wide open." The exposure is 1/320s @ f2.2 . The lens is a 50mm (Standard) which can actually go as wide as F1.4 but I wanted to make sure I got the entire brand name in focus. My light source was a compact florescent bulb about 5 inches to the right of the subject and a folded piece of white paper for a fill card on the left. The newspaper is shown below the Argus 40; it just felt right to show two antiquated but completely functioning objects together.

Can you see the isolation that shallow DOF brings? Nothing is in sharp focus outside the words Argus 40, and even there sharpness begins to fall off at the 40 ever so slightly. The newspaper is illegible (which wouldn't be the case if I was shooting at an equivalent exposure like 1/2 sec. @ F 16. At a smaller aperture DOF increases forwards and backwards from the point in which the camera is focused. Depending on your intent, DOF is one of the most important tools in photography. It helps to create a point of interest, is key as a design element, and since it is tied directly to the basic operation of all cameras, crucial for the photographer to know how to use properly. The simple act of knowing what F-stops produce greater and less DOF will revolutionize any beginning photographer. You should be the one deciding your camera's exposure, not the camera. So many of the evolutions in photography (internal metering, auto focus, zoom lenses) are wonderful tools for the skilled user, but they have become handy-caps for the novice. Photography is a science AND art. You cannot do one properly if you neglect the other in this medium.

Okay, enough ranting... anyone want to know how to about how to mimic the blue hue in the above image? I use Adobe Lightroom 2.0 to edit my images. As a wedding and portrait photographer I deal in volume and Lightroom has been a saving grace. This year alone I have processed over 64,000 images in record time thanks to this well designed software.

Here is the original image. After importing it into Lightroom I adjusted the settings under the develop tab to these amounts:

Color Temperature: 2100 Kelvin

Tint or Hue: +18 (towards the magenta end of the spectrum)

That's all it takes to fake the look to a tungsten balanced film shot in daylight. You see, the color of light is based on it's Kelvin temperature. Daylight is about 5500K and with the advent of color film came the need for multiple types of film to match the variety of light sources besides the sun. These include your regular 60 watt tungsten indoor lights, your florescent tubes and everything in between. I'm sure it didn't take long after these films hit the shelves that someone shot them outside and found a profound color shift. It's a fun trick and nice throw back to another era of photographic evolution.

If you plan to do the same thing in Adobe Photoshop here's what you need to do:

1. Create a Hue/Saturation layer

2. Use the drop down menu and select Cyanotype (yet another by gone style of yester-year)

3. Increase the saturation to the desired level. I chose 47.

Nostalgia and software aside, photography in all in the application. Tomorrow blog will focus on anther rudimentary element of photography; composition. Until then, please browse the portfolios at Irene Jones Photography Online for examples of how I've used depth of field in my wedding and portrait work.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment